Yuletide Tales of Astoria’s Holiday Past

Christmastime is here! During December, thousands of Astorians will ock to Steinway Street and Ditmars Boulevard to do their holiday shopping. There will be tree lightings and holiday gatherings (with social distancing rules in place of course) as we attempt to maintain a sense of normalcy.

As we move forward into 2021 let us take a look back at how Christmas was celebrated in Astoria during the past century. Here are some interesting and amusing anecdotes of holiday happenings in Astoria culled from the archives of the Queens Historical Society and the Long Island City Star-Journal which informed the citizens of Astoria from 1842 until 1968.

In mid-December 1914, the Star Journal reported that Long Island City planned to have “one of the most elaborate” public Christmas displays ever. The Elks Lodge agreed to host the seasonal celebration and accepted a tree nearly 50 feet high offered by City Parks Commissioner John Weier. A two-hour concert took place on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, and New Year’s Eve. Mayor Mitchel lit the tree erected in Queens Plaza, from a remote location, while Santa Claus made a surprise appearance.

In December 1917, America had joined World War I with millions lighting on the front lines in the trenches of France and Germany. Meanwhile, here in Queens, the people of Astoria were doing their share to ensure a happy holiday for the men serving. On December 28, the Star Journal reported on a special railroad car named the “Christmas Car,” fillled with packages that were sent from the freight yards of the Long Island Rail Road in neighboring Sunnyside en route to Camp Wadsworth at Spartanburg, South Carolina.

Commissioner of Public Works Richard Newcombe organized the event.

”Everyone connected with the office caught the fever and for the day the business of the borough was put aside, in order to take care of the more pressing business of making the boys at Spartanburg happy,” said Newcombe to the Star Journal. ”The presents came in all forms and sizes, from trunks, suitcases, and steel cabinets to packages measuring but a few inches in diameter. In them were clothing, fruit, candies, and safety razors; yes, lots of safety razors for the boys are not letting their beards grow to Rip Van Winkle length while they are in the south. Not a few of the packages came from persons who had no relatives at Camp Wadsworth, but who wanted to help make the boys there happy. Their packages were marked simply, ‘To a Friendless Soldier,’ and will be given to someone who has not otherwise been remembered.”

The holiday rush was as aggressive then as it is now; with thousands of commuters packing the trains of the IRT in Queensboro Plaza hurrying home for the holidays. A few days before Christmas 1918, the Star Journal printed a letter from an irate commuter, George Ross, describing his ordeal transferring to the Corona train at the Bridge Plaza: “To push through that crowd was virtually taking your life in your hands. The conduct of those men was simply disgraceful. The platforms were jammed, and in their mad rush to board the train, this inhuman rabble opened the windows and scrambled by that route into the cars by the hundreds. After about a 15-minute delay the train finally moved across the bridge. As it went by, I could see that there was not an inch of spare room on the whole train from end to end. Hundreds were left on the platform who could not even get a foothold.”

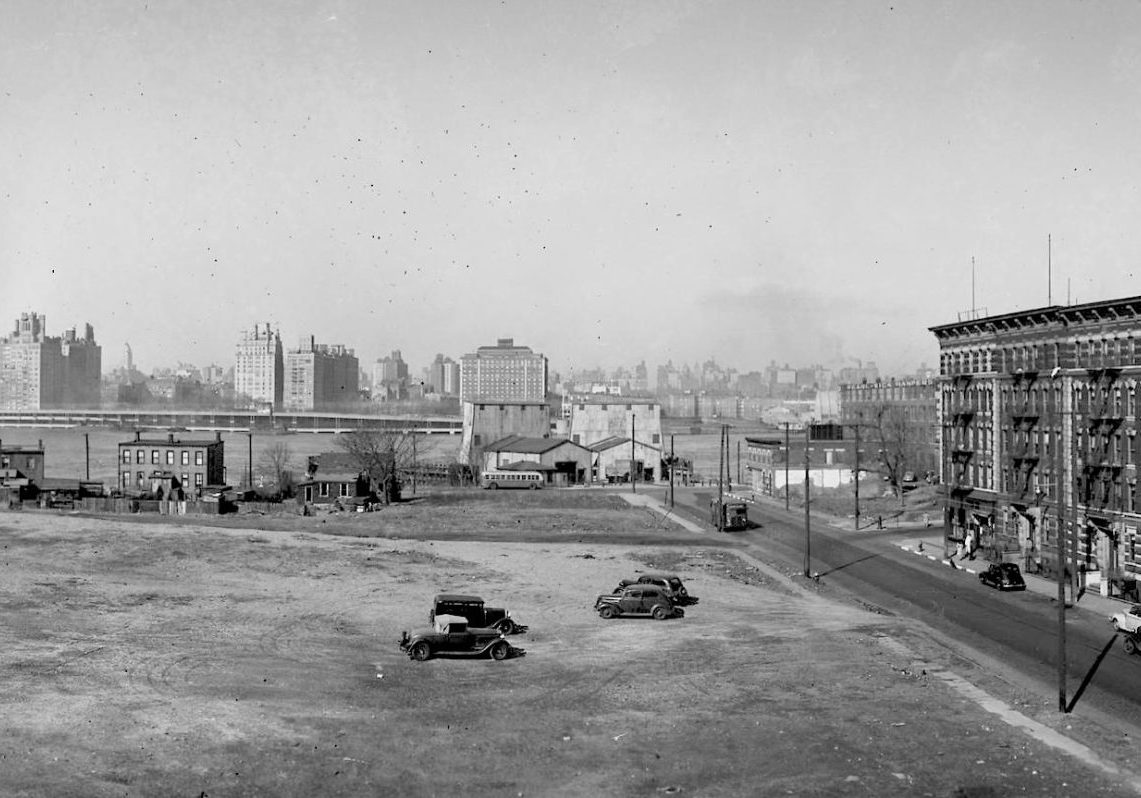

Speaking of Queens Plaza and World War I, there came an unusual site on December 21, 1918, witnessed by the people of Astoria and Long Island City. An exhibition entitled, “Hero Land”, was set up in Queensboro Plaza honoring the lighting soldiers overseas. On display, that day was, ”one of the famous tanks as used in a recent drive against the Germans. The huge monster was shipped Sunday afternoon from the Ford plant in Long Island City, where it was brought across the Queensboro Bridge from Grand Central. It had been on exhibition there at “Hero Land,” reported the Star Journal. ”The huge crawling monster with its deadly guns peeping from its armored sides attracted a great deal of attention as it made its way along the bridge and across the plaza. The crew of 9 British soldiers, escorted the tank across the bridge to the Ford plant at Jackson Avenue and Honeywell Street, where it was loaded onto a flatcar.”

Moving forward to the 1930s, the Great Depression had cast its horrible shadow on the citizens of Queens. By the winter of 1932, one in four Americans was unemployed. Stories of hardship appeared in local papers, like that of the Astoria mother of six children “with no coal and so poor that she had to knit our bags into garments for her children.” This story touched the hearts of many Astorians who contributed generously despite their own financial circumstances. Local civic organizations also did their part to help the needy in Astoria. The Star Journal reported that 30,000 baskets of Christmas food were donated by charitable organizations and political clubs to needy families in Queens.

The Star Journal estimated that a Christmas dinner for eight could be purchased for $6.44, “the cost based on the current prices of the Great Atlantic and Paci c Tea Company, whose stores throughout the nation will ll 5,000,000 Christmas dinner market baskets this year.”

On December 29, 1932, the Bliss Theater in Long Island City did its bit towards seasonal cheer by holding a free children’s matinée, sponsored by neighborhood businesses Lindy Clothes and Adams Hat.

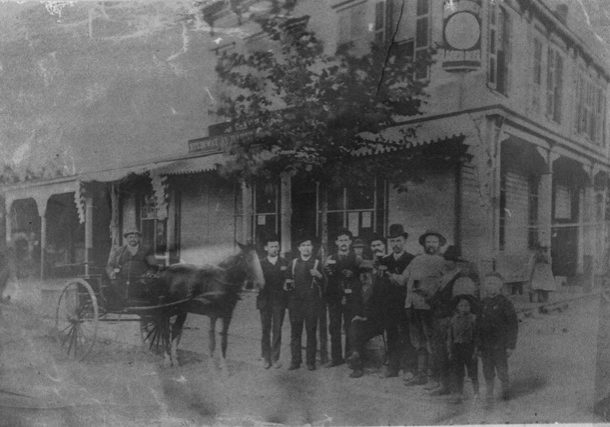

The following Christmas of 1933, was greeted with much enthusiasm as Astorians were anticipating one of the greatest holiday gifts of all. Alcohol! Throughout the borough, establishments displayed newly minted liquor licenses ready to kick o the holiday festivities with a beverage that the country had not been allowed to consume (legally speaking) for 13 years. More than 80 restaurants, hotels, and retail liquor stores were approved to sell legal liquor in Queens.

In Long Island City, two warehouses stood filled with crates and bottles valued at $500,000, its contents waiting to start happily owing to the thirsty masses. All of Astoria stood by at the ready to wet their whistle in celebration of the end of the Volstead Act – Goodbye Prohibition!

Let us remember these fascinating Yuletide tales from Astoria’s wonderful past and share them with generations to come while gathering around the Christmas tree. Happy Holidays!