Digging Up The Past: A Brief History of Archeology In Astoria Park

“Archaeologists do not discover the past; they work on what remains” – Michael Shanks, Archeologist

When one thinks of archeology, visions of dinosaur bones unearthed from layers and layers of chalky clay and sand against a desert backdrop in far away places is what usually comes to mid. However, relics of the past are everywhere and even Queens has its own Jurassic Park…Astoria Park!

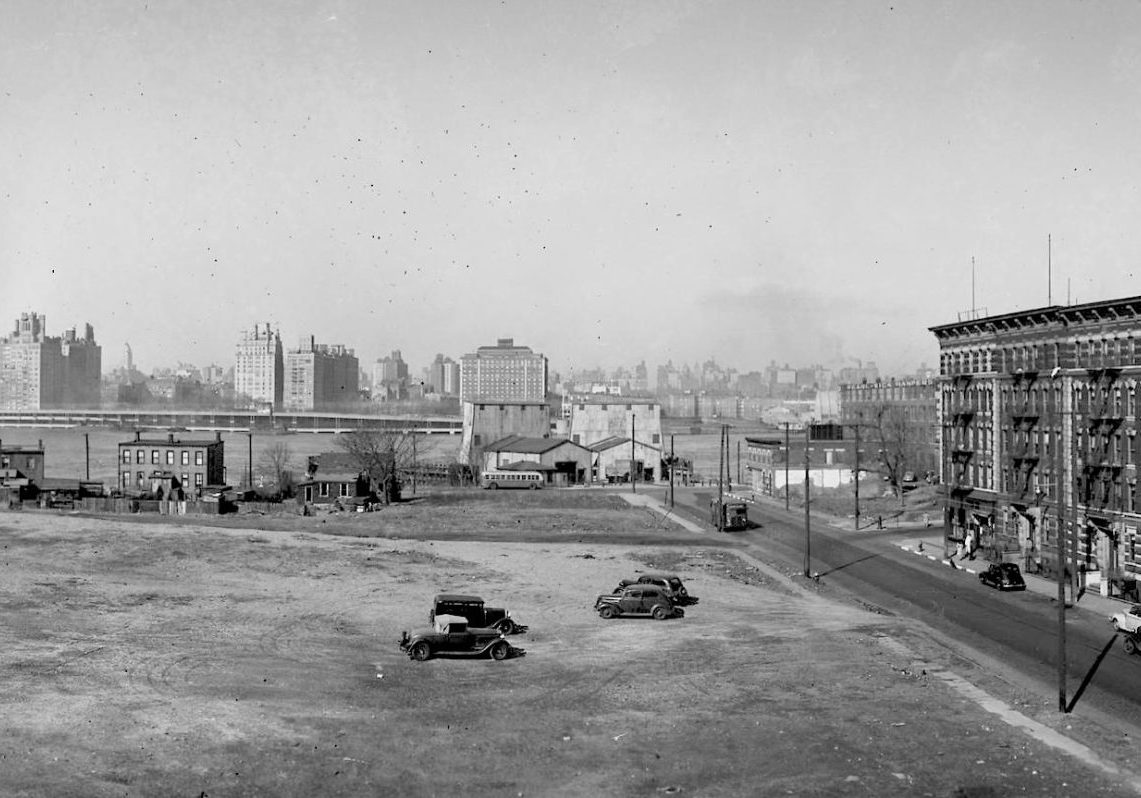

In January 1913, the NYC Parks Department acquired the 50 plus acres directly facing the East River and named it for William J. Gaynor, former mayor of New York City who was instrumental in the park’s creation. Shortly thereafter, however, it was renamed Astoria Park on New Year’s Day 1914.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote in its December 31, 1913 that Astoria Park was, “The first city park of any considerable size, in which the great question of providing space for recreation in the form of organized play versus recreation and inspiration as derived from the contemplation of landscape beauty and physical exercise in rural surroundings has been frankly faced and solved.”

Among the park’s noteworthy features is the Astoria Park Pool constructed in 1936. One of eleven pools introduced in an ambitious city-wide Parks and WPA project, the pool complex, including portions of its surrounding site, was designated a New York City Landmark in 2006. As construction of what would become iconic Astoria Park landmarks took place starting in 1917 with the Hells Gate Bridge through the late 1930s with the building of the Tri-Borough Bridge and pool, archeologist were on hand to see what secrets awaited beneath the surface through the layers of time.

Enter Queens resident Ralph S. Solecki. A native of Brooklyn, Solecki was only 20 years old and had already become one of the most sought after archeologist in America. Solecki, an influential member of the Columbia Anthropology faculty from 1959-1988, was best-known for his work in Iraq at Shanidar Cave (which he collaborated on with his archeologist wife Rose), but also carried out a great deal of research in the local New York City region. He became interested in archaeology as a teenager living in Brooklyn, when he began digging at sites on Long Island.

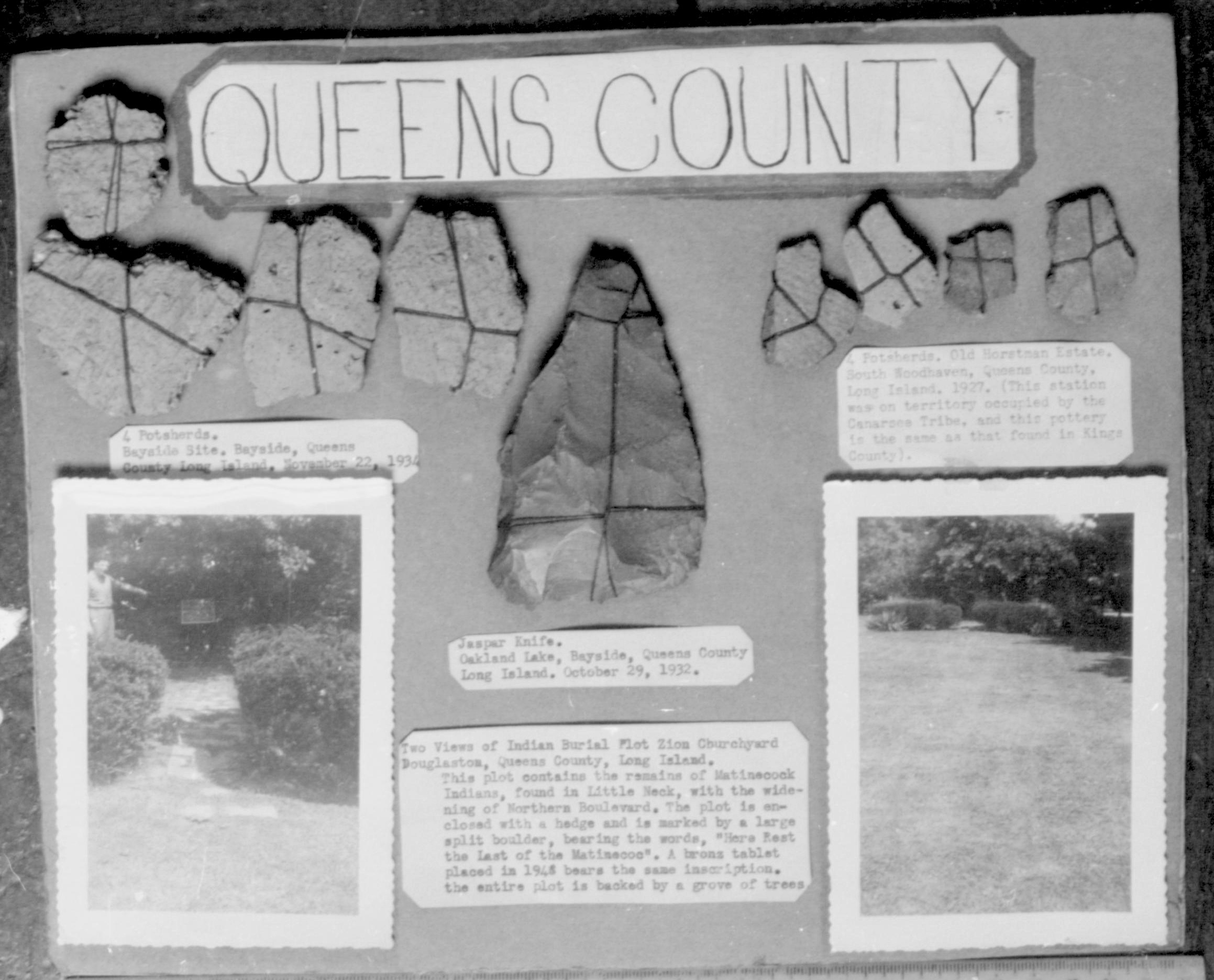

Solecki had been very involved with archeological digs along the North Fork of Long Island and had unearthed hundreds of Native American artifacts which gave greater knowledge of the Algonquin and Canarsee cultures of the Lenni Lenape peoples who inhabited Queens for thousands of years as well as the contact period when Europeans first arrived on Long Island and encountered the Native Americans.

And so he was hired to perform an archaeological assessment for the newly developing Astoria Park. Solecki knew that the park site would have been attractive to both prehistoric and early-historic-era populations due to its shoreline location which was ideal for transportation and food resources. The land also featured rolling hills and fresh water was available from the brooks and creeks that cut through the park and emptied into the East River. Among the available fresh water sources was Linden Brook, a small watercourse that ran at or near what is now the park’s southern limit. During his dig in Astoria Park Solecki and his team discovered numerous artifacts.

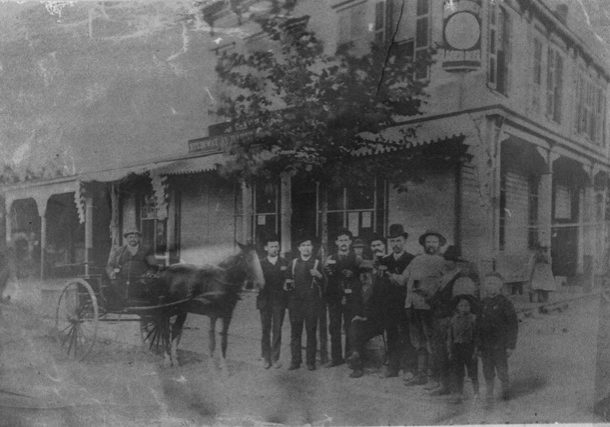

These included some remnants of the 120 year old Barclay Mansion (the last estate to exist within the confines of the park torn down in 1913); a ship’s anchor; various seashells and bullets dating back to the Revolutionary War. Approximately 10,000 British troops were stationed in Astoria Park after the Battle of Brooklyn on August 27, 1776. The previous year, Astoria residents witnessed the sinking of the Hussar, a British frigate that carried a shipment of gold after it was caught in the whirlpool of the Hell Gate River known as the “Pot Rock”.

The Hussar and its treasure have never been retrieved. As Solecki dug deeper, relics of the first people to inhabit Astoria were found including hundreds of arrowheads, fragments of pottery and shell heaps known as middens. As a result of Solecki’s efforts he, along with his colleagues, identified 75 sites throughout Queens which were once home to Native Americans of which, two sites were located right along the shoreline of Astoria Park. Solecki also discovered arrow heads and pottery near the cove between the Hell Gate and Tri-Borough Bridges. It was here that the Lenni Lenape cleared woodlands to grow corn, harvested oysters and clams, and caught and abundance of fish.

To Solecki and his team, these undisturbed finds were amazing because there is no question that both creating and updating Astoria Park disturbed the park’s natural terrain decades before. Once Solecki completed his Astoria dig he moved on to several others in Queens including one at Maspeth Creek, Whitestone and along Newtown Creek. Solecki died on March 20, 2019 at the age of 102 in New Jersey.

An interesting side note regarding the early history of Astoria Park. It was Augustus D. Julliard, a wealthy textile merchant from New York City who was instrumental in amassing the land that ultimately became the park. Julliard began to acquire property in 1872 purchasing the Hoyt and Woolsey properties. In 1905, Julliard sold the former Hoyt and Woolsey properties and all of the land along the shoreline to the East River Land Company who would in turn create Astoria Park.

However, Julliard’s legacy does not come from this shrewd land purchase. His recognition centers on the large donation he made using the money of the land sale to a music foundation that today is the Julliard School of Music.