Little Malta in Astoria!

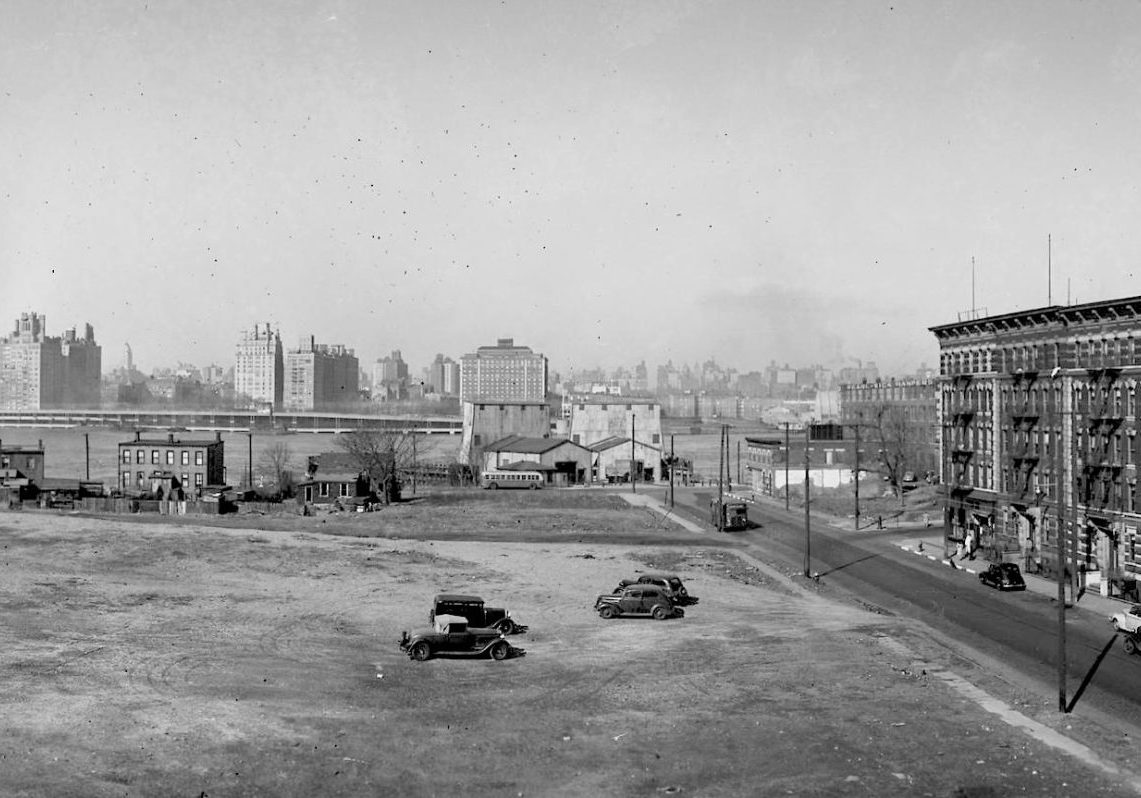

New Yorkers typically know Astoria as an ethnic enclave of Greeks, Italians, Brazilians, Colombians, and now, Midwesterners. While the neighborhood has adapted and slightly changed its identity with each succeeding wave of migration, what most people may not realize is that before Astoria was “Little Athens,” it was “Little Malta,” thanks to Maltese Americans who put their stamp on our history. In fact, the Maltese Center, an unassuming, brick building crested with the red Maltese cross at the foot of the RFK Bridge has been the gathering place for the cultural community since it opened in 1982. In 2008, the street in front of the Center was renamed “Malta Square” to commemorate the legacy of the community in the neighborhood.

The Maltese have been emigrating to the US since the 18th century. After WW1, a surge of immigrants came at the heels of the closing of the Royal British Dockyard in 1919, first settling in New Orleans, then Detroit, then NYC and other major cities like San Francisco and Chicago. After WW2, the Maltese government encouraged emigration when it agreed to pay for passage to the US. As a result, close to 10,000 Maltese came to America between 1950 and 1970; massive for a nation that averaged 350,000 citizens over 122 square miles. And thus, Astoria became home to a Maltese community.

Malta itself, nicknamed the “mouse that roars,” is an archipelago of seven islands, but its main three, Malta, Gozo, and Comino, are famous for their grottos: the shipwreck of St. Paul and the pivotal part it played in the Crusades and in WW2. At the crosscurrents of the three islands, Malta has held a strategic post in the Mediterranean since ancient times when Phoenicians settled there. Maltese heritage is often confused with Italian, but its roots are actually Arabic from the Levant mixed with Italian and French.

Long-time Astoria resident Charles Scibberas, whose parents moved to Astoria in the 1950s, has been a real estate agent in the neighborhood for 45 years. “Once you are a Maltese, you are a unique human being because of your history,” he says. He can trace his own history to Egypt and Mount Sciberras, the hill where a citadel stands in the capital of Malta, Valletta. He claims his physical features can be traced to an illustrious ancestor whose portrait can be found there in a piece of artwork called “The Great Seige of Malta” by El Greco.

Scibberas explains that NYC’s first Maltese immigrants lived on 23rd Street and 1st Avenue near Beth Israel, attracted to Astoria for its sense of community and the chance to own their own single family homes instead of cramped apartments. He remembers the Maltese coming from all over Queens to play soccer on Sundays in a field outside LaGuardia Airport: “After that, we would have BBQ and spaghetti with rabbit” rabbit being a staple dish in Maltese culture. In fact, the rabbit stew cooked at the Maltese Center on special occasions, “stuffat tal-Fennek,” is one of the oldest Maltese recipes in existence, dating back to Phoenician times. According to Scibberas, the Maltese found it easy to fit in with the other Mediterranean cultures that made up Astoria because of the shared value in keeping close family ties.

While many Maltese Americans have taken the path toward upward mobility that their hard work has garnered them by moving out of Astoria and into the suburbs, there are still vestiges of the Maltese community among us. There was Joe Galea, famous for the Maltese Bakery on 36th Avenue, who employed hundreds of workers. There used to be a Maltese-American Friendship Society on 45th Street between Broadway and 31st Avenue and even a Maltese auto repair shop on 34th Avenue and 42nd Street.

Today, besides the Maltese Center, there still stands Leli’s Bakery on 30th Avenue. Sometimes mistaken for Italian, bakery owner Emanuel Darmine, now in his 70s, continues to keep Maltese staples on his shelves; there’s the pastizzi, a flaky pastry dough covering several fillings, some savory, some sweet; the pezili pastizzi with a filling of meat and peas; the more popular juben filled with ricotta; and the spinach and feta pastizzi. And we can’t forget the Atalasa or molasses ring, a sweet that dates back to the Arab/Phoenician traders that’s filled with dates and semolina.

The Maltese Center is open on weekends and welcomes any and all visitors. If the kitchen is open, you can get pastizzi and various other great fare. September 8th is National Malta Day and there are traditional dances and other festivities planned, so be sure to stay tuned!

More info on the Maltese Center: Click Here