LIC Was Once The Land of Terra-Cotta

It’s one of the finest examples of historic preservation in the entire city. And you’ve probably walked right passed it. The former main offices of the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works, built in 1892 and designed by Francis H. Kimball, sits all by its lonesome along Vernon Boulevard just underneath the Queensborough Bridge.

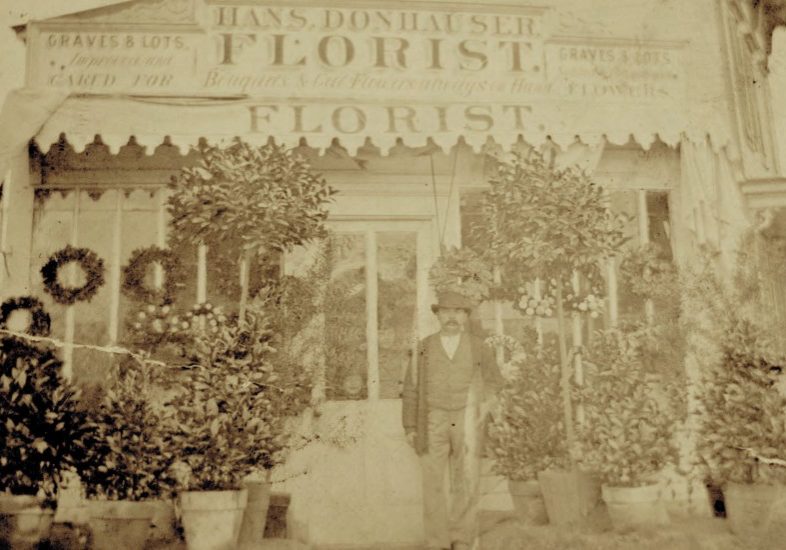

The former offices of the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works has stood just beneath the

Queensboro Bridge on Vernon Boulevard since 1892.

The NYATCW was in operation at what was then known as No. 401 Vernon Avenue in Long Island City, from 1886 until 1968. Of the forty-eight major terra cotta manufacturers in the United States, it was the only such plant situated in New York City. The NYATCW supplied architectural terra cotta for projects throughout the United States and Canada. Materials supplied from this location were used in constructing more than 2,000 buildings. Among the company’s most prominent contracts included Carnegie Hall and the Ansonia Hotel. Terra cotta became popular as a building material in the United States beginning in the 1870s and enjoyed a long tenure due to its flexibility, versatility, and durability.

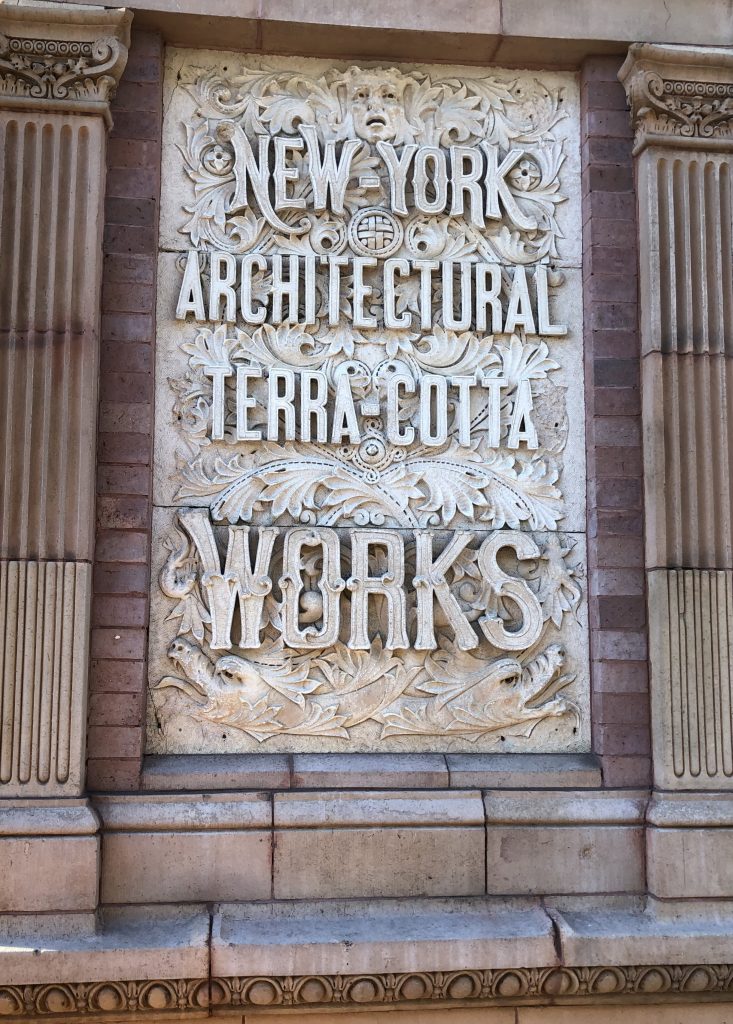

Photo 2: The crown jewel of the preserved building was the relief which reads New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works.

Established in 1886, the company was the only major architectural terra cotta manufacturer in the city and at the time of the building’s completion the facilities were the largest in the country for architectural terra cotta. The company set up its manufacturing operations on the Long Island City waterfront in 1886 and initially kept an office at 38 Park Row in Manhattan. Six years later, its office headquarters were moved to this remarkable building, whose design served to advertise the company’s considerable range and skill with terra-cotta.

In his 1891 book, Terra-Cotta in Architecture, Walter Geer (who would later become the company’s president) described the factory in detail. “The first story contains the engine, boilers, machinery for preparing clay, and the clay, coal and grit pits.”

This machinery at the facility included washer and slip tanks, crushers, and mill stones, as well as some items known as pug mills. There were 12 kilns in which the terra-cotta was prepared. The clay used was mined in New Jersey. It was delivered to the factory, where it was crushed, ground, washed, and mixed with grit before being molded and sculpted. From there, the terra cotta was used to adorn some of the most beautiful buildings in the city. The company went bankrupt in 1928-29, but from 1931 to the mid-1940s, the company’s last president, Richard Dalton, used the facilities for his successor company, the Eastern Terra Cotta Company, and then conducted business for a later construction company venture in the headquarters building until his death in 1968. The Dalton family sold the building that year and the rest of the complex, which included a six-story manufacturing building and the mansion of an estate previously located on the property, was unfortunately demolished in the 1970s.

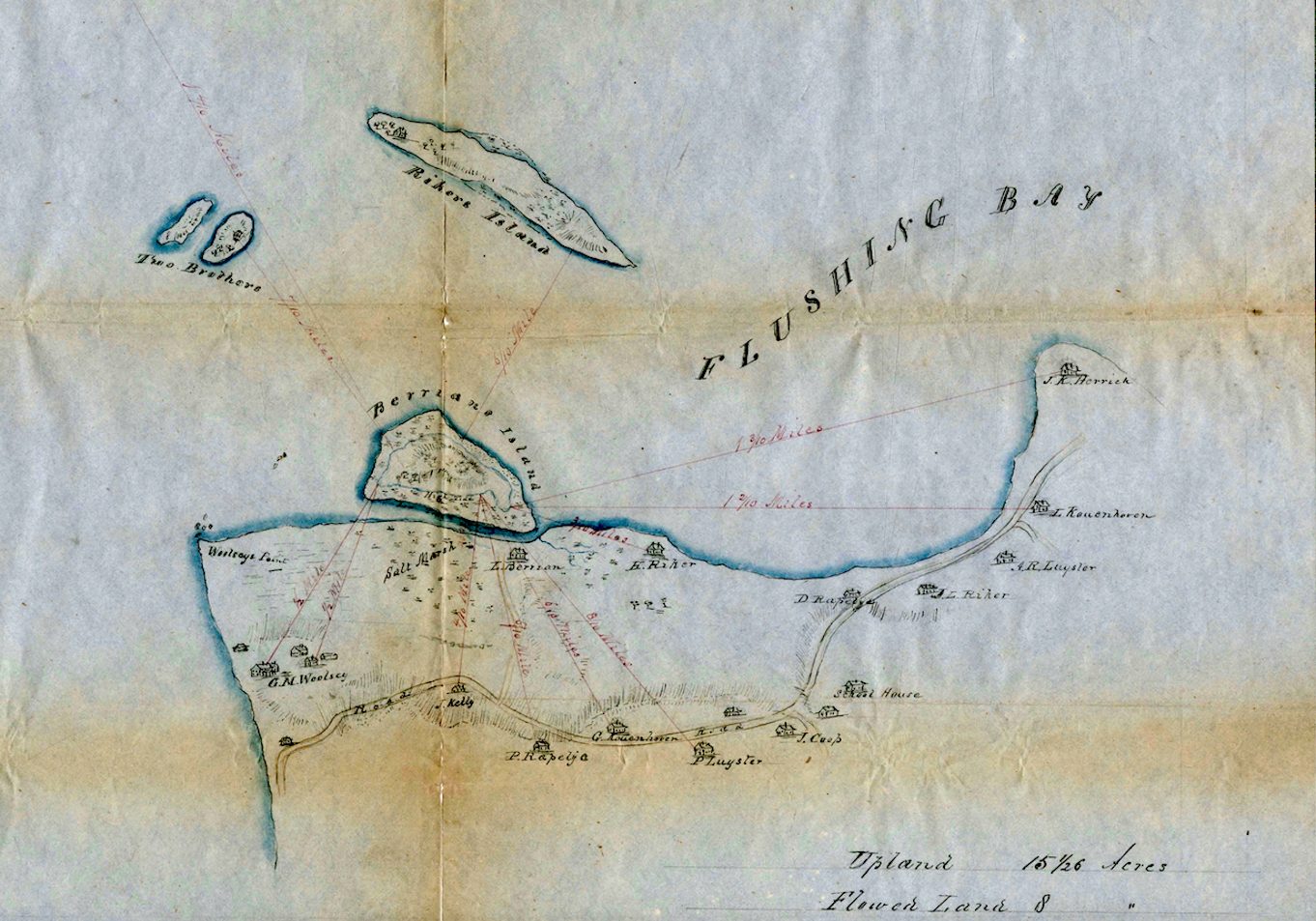

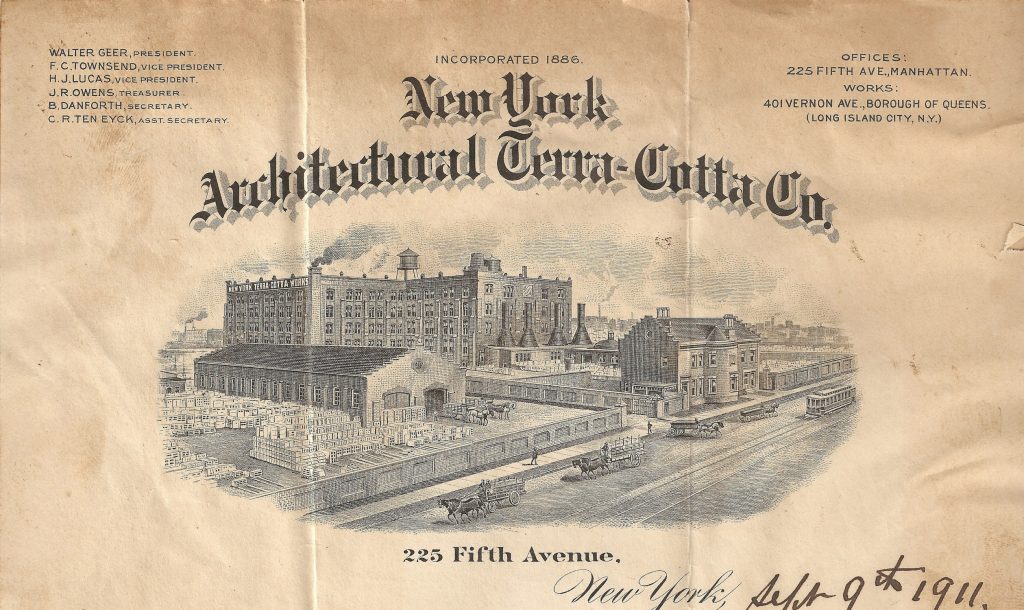

A letter head from the New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works shows the once enormous complex along Vernon Boulevard. Notice the absence of the Queensboro Bridge for it would not be built until 1909.

The crown jewel of the preserved building was the relief which reads ‘New York Architectural Terra-Cotta Works’. A plaque featured above reads in Latin, ‘Anno-Domini 1892′. At the right end on the main floor, is a doorway marked “Office” in raised letters. Just below the gutter and the tiled roof runs a frieze of whimsically grotesque faces emerging from leaf work along with the original address number of the building, No. 401.

Photo Jason D. Antos

A plaque featured above the main doorway reads in Latin, Anno-Domini 1892.

The best description of the building is summed up by a 1987 New York Times article by Christopher Gray who wrote, “The entire building is a rich symphony of hard-burnt brown, cream and umber.” Although now fully restored the future of what was once the nation’s leading manufacturer of terra-cotta is still unknown.